What is it about cursive that can make us crazy?

This post may contain affiliate links.

Cursive handwriting is like a sleeping dog…don’t wake it up unless you want to hear some barking! As innocent as it may look, it conceals a great deal of energy and power. It certainly must because it can cause a lot of discussion among handwriting advocates. Discussion is a good avenue for sharing and learning and that’s just what we found with the publication of my previous blog post, “Cursive Handwriting’s Link to the Leaning Tower of Literacy.” In the interest of continued learning and the further exploration of cursive handwriting’s legacy, we will take a look into the links and resources that were shared by our readers and interested professionals. As we go along, I will also share some of my own personal opinions (of course!) related to some of this information. I hope you will enjoy the ride into Cursive Land and will feel free to join in the discussion!

Cursive handwriting is like a sleeping dog…don’t wake it up unless you want to hear some barking! As innocent as it may look, it conceals a great deal of energy and power. It certainly must because it can cause a lot of discussion among handwriting advocates. Discussion is a good avenue for sharing and learning and that’s just what we found with the publication of my previous blog post, “Cursive Handwriting’s Link to the Leaning Tower of Literacy.” In the interest of continued learning and the further exploration of cursive handwriting’s legacy, we will take a look into the links and resources that were shared by our readers and interested professionals. As we go along, I will also share some of my own personal opinions (of course!) related to some of this information. I hope you will enjoy the ride into Cursive Land and will feel free to join in the discussion!

What IS cursive, anyway? It appears that even Merriam-Webster has some difficulty defining it. They flip-flop between “flowing often with the strokes of successive characters joined and the angles rounded” and “a style of printed letter resembling handwriting.” As we all know, a handwriting style is very personal, ranging from manuscript letters alone, to manuscript letters connected to each other, to a mix of manuscript and “flowing joined letters,” and finally to the “traditional” cursive that Spencer, Palmer, and Zaner brought to life in the 1800’s. With that said, I feel that Merriam-Webster’s most accurate definition of cursive is the one they describe as “a type of handwriting in which all the letters in a word are connected to each other.”

Although the defining of cursive may seem incidental, it is in fact a significant player in the tag-team discussions of handwriting instruction. Therefore, it warrants the need for clarification. In my original blog, I referenced the following information obtained from a site sponsored by a proponent for teaching Cursive First:

“…given the fact that Great Britain is the only country in Europe who doesn’t teach cursive first, and that the European literacy rate has not suffered by the introduction of cursive first, couldn’t we save precious educational time by simply teaching cursive right from the start?”**

Kate Gladstone, owner of Handwriting Repair, and a valued colleague, shared an enlightening lesson in cursive in her comments to my article. Her research has found that numerous countries in Europe teach a “separate-letters style” of handwriting as their introductory stage for children, mandatory for some and elective for others, followed by their choice of a semi-joined or joined form of “cursive.” In addition, cursive – the picture in one’s mind’s eye of cursive – takes on a different form as we travel through these countries. Brian Hagerty, in his article, “Handwriting: Methods and Resources,” demonstrates that the “cursive” which is taught in Finland can be very different than the one that students learn, say in Britain or France. Kate points out that “the writing forms whose names are usually translated into English as ‘cursive’ would not, in fact, be regarded as ‘cursive’ by proponents of cursive handwriting in the USA or Canada….” She asks us to note that:

“the same circumstance (of “cursive” not being what you thought it was) is usual, not merely in Europe, but throughout the English-speaking world outside of North America. About half of the writing methods taught as “cursive” in the UK, and about 85% of the writing methods taught as “cursive” in Australia and New Zealand, are semi-joined and with print-like forms of most or all the letters that disagree between printing and cursive.”

In that light, wouldn’t we be wiser to think of cursive handwriting as “unjoined and joined,” without qualification for consistency in style? For the sake of argument, let us stay the course with this definition.

I say this because the argument for-or-against the teaching of cursive remains to be an issue. Hence, the simple re-defining of cursive is a starting point and not the final destination. Since I am an advocate for keeping cursive alive, let’s start with some facts that I’ve found through my research over the years.

Manuscript was not the first handwriting style to be taught in the United States. Although it has claimed the first seat in handwriting instruction, it is a relatively new visitor on the educational scene. In fact, manuscript printing was introduced in Europe less than 100 years ago, with the idea that “keeping the letter formations simplified to primarily circles and straight lines would be much easier for young children to learn and produce.” The process was considered initially to be an introduction to learning cursive later. In the spirit of history repeating itself, it is ironic that educators in the 1900’s became concerned when children who learned primarily manuscript (with many of them not returning to school for cursive due to family responsibilities) could not read anything written in cursive. They found this to be unacceptable, realizing even 100 years ago that “this was a dumbing down of the education process.” In the end, many chose to reverse the decision to teach manuscript, aligning with the many countries that never taught printing at all. The decision to return to the teaching of cursive from the start in this case stemmed from the literacy levels of the students who were not afforded the benefit of long-term education. Today, this seems to be invalid, as Kate Gladstone, in a comment on her Facebook Page, reports that “reading cursive can (and should) be taught in just 30 to 60 minutes — even to five- or six-year-olds, once they read ordinary print.” So, let’s move on to the importance of teaching handwriting at all.

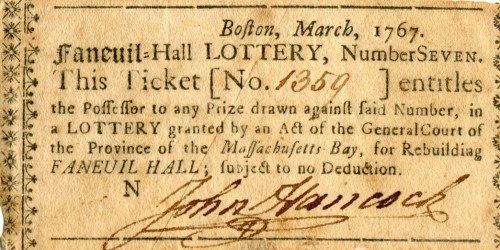

Prior to the 19th century in handwriting history, quality penmanship was considered to be a necessity for businessmen and ladies of culture. In the American Colonies, a “good hand,” as it had come to be known, was deemed “a sign of class and intelligence as well as moral righteousness.” However, this indicator of class, intelligence, and righteousness was only available to wealthy men and businessmen. The beginning of the 19th century brought about universal schooling in the US and the inclusion of handwriting in the curriculum, introducing “class, intelligence, and moral righteousness” to every student. Despite the “righteousness” of this thinking, the availability of handwriting instruction goes far beyond one’s ability to produce a pretty signature.

A 2012 study conducted by Laura Dinehart, an assistant professor at Florida International University’s College of Education, and published in the Journal of Early Childhood Education and Development, found that “kids who have greater ease in writing have better academic skills in the 2nd grade in both reading and math.” Study results showed that students who received good grades on fine motor writing tasks in pre-k had an average GPA of 3.02 in math and 2.84 in reading – B averages – versus 2.30 and 2.12, respectively – C averages – for those who did not. These students also scored in the 59th and 62nd percentiles on the 2nd grade Reading and Math SATs, respectively, versus 38th and 37th for those students who did poorly. Of course, this study was conducted in the US, hence with students who learned manuscript. Would it have mattered if they had been learning a “joined” handwriting style? A question I have yet to have had answered!

My reference to Professor Steve Graham’s research in my previous blog was to share information that points to legibility and effective communication being more of a concern than the handwriting style being taught or used to convey a message. In answer to the question, “Should Schools Keep Teaching Both Cursive and Manuscript Handwriting?“, Professor Graham suggests that, first, there is a strong “behavioral case” for why we teach handwriting at all, “based on what the effect is on writing itself.” Handwriting, in my opinion, is simply the conduit for moving our thoughts from our brains to our hands and, finally, to a piece of paper. If the handwriting is cursive, manuscript, italic, or hieroglyphics, and it isn’t legible, it is worthless. Graham stresses this in his remark:

“If your handwriting isn’t very legible, people form pretty strong ideas about the quality of the composition. That effect is so strong that if you were to take an average piece of writing that was somewhat difficult to read and made it legible, you could move that piece of writing almost all the way to the top of the pack. If you were to take that piece of writing and make it very difficult to read, you could move all the way to the bottom of the pack without changing one word in the paper. These are really strong effects. Also, if your hand can’t move fast enough with your mind, you lose ideas.”

Although Steve Graham, in his article “Want to Improve Children’s Writing? Don’t Neglect Their Handwriting,” states that “research does not provide a definitive answer about the relative effectiveness of different scripts,” he does indicate that the fact that children come to school with a knowledge of manuscript lends that style to be a more effective one upon which to place emphasis. He also refers to research (although dated) that indicates that “traditional manuscript is easier to learn than cursive” and that once it is mastered, it can be written faster and possibly more legibly than cursive. However, it has been said that as writers mature, in age and proficiency, they adopt their individual style of handwriting, often producing a combination of printing and cursive, or simply linking their printed letters together, resulting in a fluid and legible method of communication. I contend that this is true and that, as we become fluent in handwriting (any style), we find the most efficient way to use our hands and arms to produce our message.

Let’s return now to “what cursive is” and the relative significance of teaching it first or at all. Kate Gladstone and I agree on a major point: there is no “A-Number-One” handwriting style that would “prevent all errors of teaching and learning in the subject” (to quote Kate). Although for some the style of handwriting being taught is important, I have found that the handwriting program itself, whether it is manuscript or cursive (joined), is not the deciding factor for success, initially or in the future. There are two deciding factors that, if not addressed from the start, make this whole discussion pointless.

1. The chosen handwriting program must be taught with consistency, close observation, and guided practice. Daily class instruction, home practice, and one-to-one mentoring are key elements.

2. Students who are not able to master their handwriting skills with age-appropriate instruction and adaptations designed to help them learn through their individual learning style should be referred to an occupational therapist for assessment to determine any possible underlying causes for handwriting struggles.

Let me point out, at this juncture, that I am an occupational therapist with a focus on the assessment and remediation of children’s handwriting skills. When parents bring their children to me, they are experiencing difficulty mastering these skills with age-appropriate instruction in school and at home. My job, then, is to tease out the hidden underlying causes for the visible symptoms. As I mentioned in my comment on my previous blog, “my current concern is more about the availability of cursive/joined letter writing styles that allow students who are not successful with manuscript to succeed with handwriting skills.” But, I would much rather that handwriting be taught appropriately from the start (joined or unjoined), and that students were “getting it right the first time!” I would love to be out of a job!

**Note: Communication with Elizabeth FitzGerald, at SWRTraining, Cursive First, has revealed that the website will be updated to reflect the research provided by Kate Gladstone.

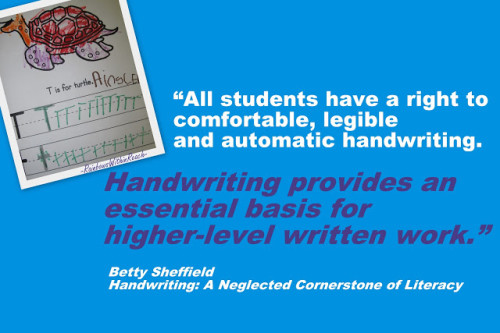

(1) Sheffield, B. “Handwriting: A neglected cornerstone of literacy,” Annals of Dyslexia, 1996: Vol 46, Issue 1, pp. 21-35.

Katherine J. Collmer, M.Ed., OTR/L, is a pediatric occupational therapist who specializes in the assessment and remediation of children’s handwriting skills. She can be contacted via her website, www.handwritingwithkatherine.com.

I listened to a John Hannity radio show the o ther day with a guest discussing research on learning print and using cursive activating different sections of the brain and that cursive helps the content to be engrained in our memory better (even if it is illegible). She also addedd that typing does not not activate the brain. i am trying to get copies of the show and links to the research as I am a school-based occupational therapist and see cursive time being shortened andtechnology and typing being pushine into our preschool-1st grade student body.

Marlene, Thank you for reading and sharing your comments. Steve Graham, a professor at the University of Arizona, has completed some good research on the link between handwriting and writing/learning in school, as well. Search for his name and you will find his work. He conducted the research while at another university; but you will know it’s him by the topic. One is titled: “Want to improve children’s writing? Don’t neglect their handwriting.” Keyboarding has a role in our students’ lives; but handwriting practice can help them to build the skills they will need for literacy. Best of luck in your work.